| A Day in the Life - Adolf Bitterlich |

|

| Written by Claude Adams |

| 28 July 2023 |

|

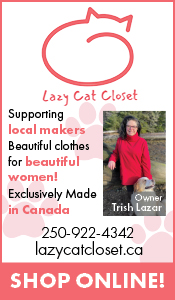

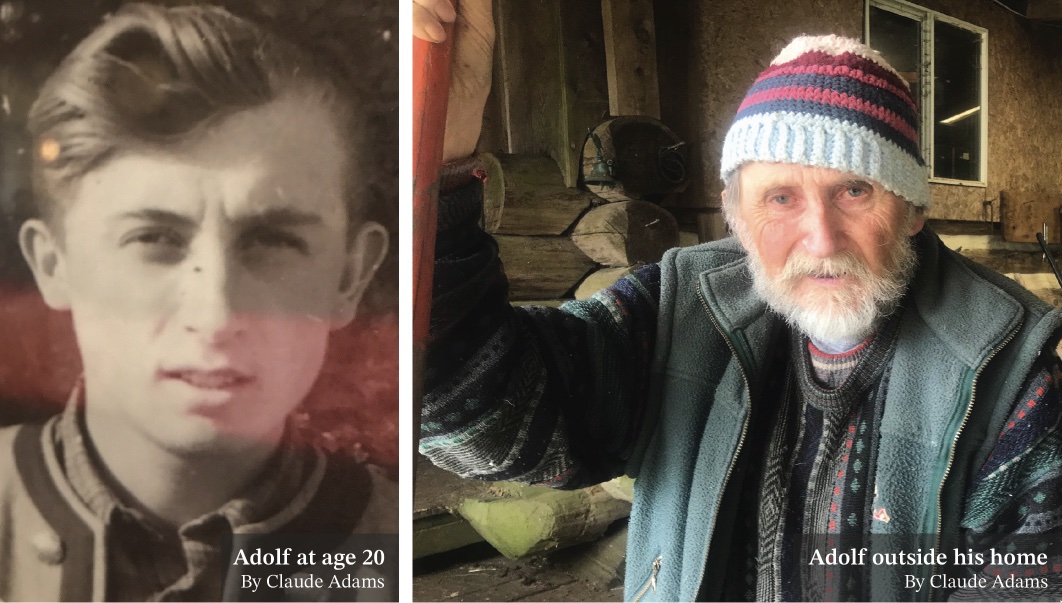

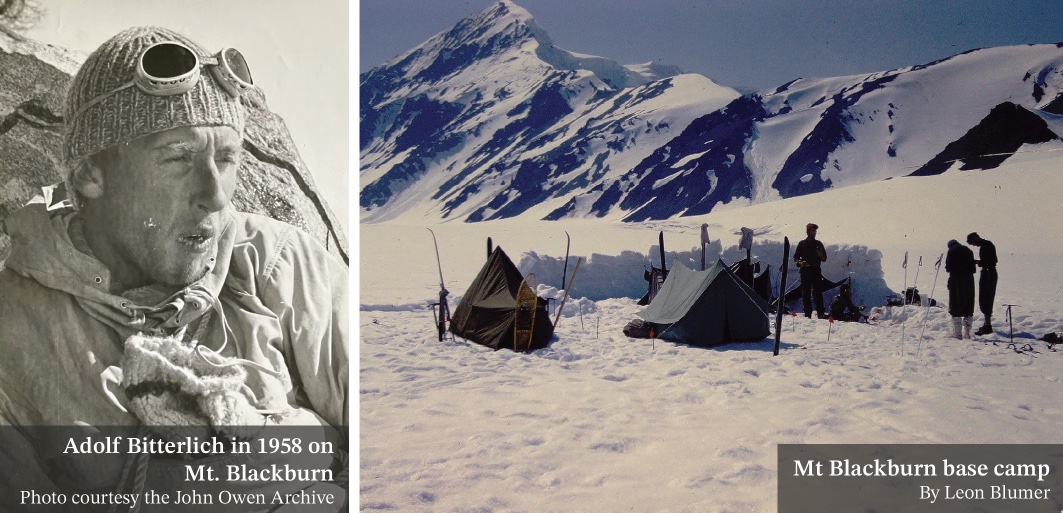

Remembering doesn’t come easily anymore for Adolf Bitterlich. At age 89, revisiting his past is a bit like groping along the walls of dark cave. But one memory is still vivid and brings a light to his eyes: His last climb, 17 years ago, up a 9000-foot mountain in west-central BC, as a guest of the Alpine Club of Canada. That ascent of Mount Howson in the Coastal Range at age 72, well past his prime, capped a glorious career as a climber and adventurer. And it was a profoundly emotional experience. “I was crying,” recalls Adolf. “It was not easy, but I was able to do it once more - that is happiness. You can cry when you have happiness. My whole thinking at the time was what I had done as a young man.” Today, Adolf lives on a small acreage in Tl.aal Tlell with two Blackface sheep, a pair of noisy geese, a cat and a few pigeons. (His flock of sheep was ravaged last year by a hungry black bear. “Bears have to eat too,” he says wryly.) He invites visitors into his rustic log cabin with a cheeky warning: “Watch where you step. I don’t have insurance.” But what he does have is a wealth of rich stories which he will tell you, slowly and deliberately and in fragments: How he walked away from two crashes in his small plane, how he liked to fly under bridges - “the things you do when you are a young man to show off” - and how he once landed his aircraft on a highway “because highways are there to land on!” However, Adolf turns serious when telling how he climbed Mt. Howson in 1958 in search of the body of another climber, Rex Gibson, killed in a fall during an ascent a year earlier. Adolf recalls a conversation he had with Gibson’s wife before his expedition. “His widow asked me not to bring his body out because they had this arrangement that he wanted to be buried in the mountains (if he was killed while climbing.) So, I made sure of that.” Instead of bringing back the body, Adolf built a cairn in Gibson’s memory near where he died.

Adolf and his brother Ulf were the first Canadians to scale Mt. Waddington, BC’s highest peak. They climbed without all the paraphernalia of modern mountaineering - the fancy harnesses, lightweight ice axes and ropes, boots and helmets commonly used today. Climbing was much more physically demanding then. “You have to earn the mountain,” is how Adolf puts it. He was born in Dresden, the capital city of the German state of Saxony, and he remembers the fire-bombing of that city by Allied aircraft when he was 11. And he recalls the tumultuous greeting when Adolf Hitler came to visit. “I remember thousands and thousands of people going ‘Heil Heil Heil’ and my grandmother when we got home said to me ‘Did you wave at Hitler?’ And I said: ‘I don’t like Hitler. I waved at him and he didn’t answer!’” Adolf left school at 14 and learned carpentry - “after the war everything was kaput and we needed carpentry.” Three years later, he bicycled 500 km to Stuttgart in what was then West Germany to train with a mountain rescue group. He earned the group’s highest award.

Adolf was married three times, and he has two daughters and two grandsons. In poor health and hard of hearing, he acknowledges that he’ll have to let his property go soon. “I can’t go on for very much longer,” he says wearily. As a devotee of the spiritualist philosopher Rudolf Steiner, he says he is unconcerned about the end of life. “It doesn’t matter how you die, there always will be something from you (remaining). . . In what form we don’t know. It can be a kernel of sand. It can be lightning.” Or it can be in the form of a collection of stories, of a man who left his indelible mark on some of the West Coast’s highest peaks. “We human beings are connected to the past,” is Adolf’s personal summing- up. “We are the makers of good and bad things. In the end, it’s up to us.” |

In Canada, he worked as an alpine guide, a logger and he ran a hobby farm. But climbing was always his primary passion. He was only 20 when he was asked to climb Mt. Arrowsmith on Vancouver Island to recover the bodies of two pilots who had crashed in the mountain. “I brought the bodies out and I became quite famous,” he says. “But it’s very difficult to tell that story so I don’t want to think about it anymore.” He was still too young to celebrate the recovery with a beer in a local bar, but an RCMP officer escorted him anyway and bought a round.

In Canada, he worked as an alpine guide, a logger and he ran a hobby farm. But climbing was always his primary passion. He was only 20 when he was asked to climb Mt. Arrowsmith on Vancouver Island to recover the bodies of two pilots who had crashed in the mountain. “I brought the bodies out and I became quite famous,” he says. “But it’s very difficult to tell that story so I don’t want to think about it anymore.” He was still too young to celebrate the recovery with a beer in a local bar, but an RCMP officer escorted him anyway and bought a round.